EQing in Octaves: Part 1

This is the first of a three-part email series designed to simplify your approach to EQ and help you make better mixing decisions.

We measure sound frequencies on a logarithmic scale in Hertz (Hz), or cycles per second. While essential for describing audio, this unit can feel abstract and disconnected to how we think about and create music. For example, a frequency of 100 Hz means a sound wave vibrates or oscillates for one full cycle at 100 times per second.

This is the first of a three-part email series designed to simplify your approach to EQ and help you make better mixing decisions.

We measure sound frequencies on a logarithmic scale in Hertz (Hz), or cycles per second. While essential for describing audio, this unit can feel abstract and disconnected to how we think about and create music. For example, a frequency of 100 Hz means a sound wave vibrates or oscillates for one full cycle at 100 times per second.

Musical notes are sound waves oscillating at specific cycles per second, and an octave is simply doubling or halving those oscillations to move up or down the scale.

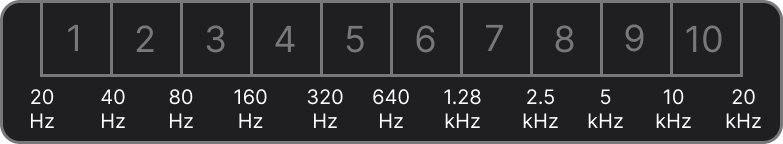

Here’s where it gets tricky: there are only 12 notes in an octave, regardless of whether you're looking at 30–60 Hz or 3,000–6,000 Hz. This is because octaves follow a logarithmic scale—frequencies double with each octave (e.g., 20 Hz, 40 Hz, 80 Hz, 160 Hz, and so on)

This doubling can seem daunting, especially on an EQ graph, but understanding it can simplify how you approach EQing and balancing a mix.

Simplifying EQ: From Hertz to Octaves

The human ear picks up frequencies from 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz—a pretty wide range. But sound doesn’t stop at the limits of our hearing range. There are sound waves below what we can hear (infrasonic) and above it (ultrasonic). However, these low frequencies are usually filtered out by DC filters, and high frequencies by anti-aliasing filters, depending on the sample rate, of course.

Focusing on what we can hear, if we think in terms of musical octaves instead of raw numbers, that big range of 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz boils down to just under 10 octaves. That’s 10 manageable “bands” to work with, instead of 20,000 individual frequencies. Much easier to wrap your head around, right? Those 10 octaves can be broken down like this...

The 'middle' frequency of our hearing range, numerically speaking, is around 640 Hz—an unexpected midpoint, but it makes sense when we think in terms of octaves. There are about 5 octaves below 640 Hz (down to 20 Hz) and 5 above (up to 20 kHz), meaning our hearing is split evenly in terms of octaves.

Relating EQ to musical octaves makes frequency adjustments feel more intuitive and grounded in how we naturally think about music. When EQing, I typically cut with narrower bands, often about an octave wide, to address specific issues. On the other hand, when boosting, I prefer using wider bells, spanning two or more octaves, to shape the tone more musically.

However, not all octaves are perceived equally. Our ears are most sensitive to the 1–5 kHz range (roughly octaves 6–8 on the frequency spectrum), where our hearing is naturally tuned to detect detail—an evolutionary trait that likely developed for survival. This range encompasses the majority of human speech, and our sensitivity to subtle nuances within it has been essential for communication and fostering social bonds throughout history.

That may be a bit too much evolutionary context for this conversation about EQing your mix, but this 2.5-octave range demands our attention. Our ears are particularly attuned to this area and are highly sensitive to imbalance, excessive transients, and shifts in loudness. Getting it right can dramatically affect how the listener perceives loudness, balance, and presence in your mix.

Thinking in octaves can transform your approach to EQ, shifting it from a technical grind to a more natural, gestural, and musical process. By mastering the fundamentals of EQ, compression, and saturation, you’ll discover that many “problem-solving” tools—like resonance suppressors (e.g., Soothe 2)—are often used to address balance issues that could be resolved with better EQ techniques. While these tools have their place in specific scenarios, they are frequently overused in modern music production.

By understanding how octaves relate to the music we create, you can map your EQ decisions more effectively to the issues you hear in a mix. This empowers you to make more informed choices and reduces reliance on complex modern resonance tools, which can inadvertently introduce unwanted artifacts that often go unnoticed.

In Part 2, we’ll dive deeper into the individual frequency bands. We’ll talk about common issues, how to tackle them, and how to keep your mixes musical and balanced.

Have questions? Just hit reply, and we’ll get back to you. You can also tag us on instagram—we’re always happy to connect!

Be well,

Ryan Schwabe

Grammy-nominated and multi-platinum mixing & mastering engineer

Founder of Schwabe Digital

Reviving Loud & Limited Pre-Masters with GOLD CLIP

As a mastering engineer, I’m often handed mixes that are already limited or clipped. These loud, finalized mixes can be tricky to work with because there’s often very little headroom or transient detail left. What I do as a mastering engineer involves envelope or dynamic shaping just as much as balancing, sweetening, and preparing a mix for distribution.

As a mastering engineer, I’m often handed mixes (pre-masters) that are already limited or clipped. These finalized mixes can be challenging to work with because they are already heavily limited, leaving little transient detail. As a mastering engineer, my work often includes envelope and dynamic shaping just as much as balancing, sweetening, and readying a song for distribution.

The Challenge of Loud Mixes

When I receive loud mixes, my ability to shape the envelope is reduced because the transients have been chopped away beforehand. While I usually request a separate, lower-level pre-master for more flexibility in handling transients, some mixing engineers prefer to stick with their loud mixes—and that’s perfectly fine.

The question is: what purpose does a clipper serve in a mix that’s already limited and clipped?

You might think a clipper has no role here. After all, if the transients are already clipped or limited, what more could a clipper possibly do? The answer lies in what makes Gold Clip so much more than just a clipper.

Gold Clip: Not Just a Clipper

Gold Clip isn’t just a traditional clipper—it’s a versatile tool equipped with internal processors specifically designed to refine limited or clipped signals, making it perfect for handling loud pre-masters. Every element in Gold Clip is bypass-able, allowing you to adapt it to the needs of your mix. For tracks that are already clipped or limited, you can turn off the clipping and saturation components while leaving on Box Tone and Alchemy. These processors can then work independently to smooth and soften clipping artifacts.

In my latest YouTube video, I explain how I use Box Tone and Alchemy to smooth and refine heavily limited or clipped mixes.

What You’ll Learn in the Video

🎛️ How Modern Box Tone smooths the top end, filters out harsh ultrasonic frequencies, and refines loud mixes.

⚙️ How Alchemy dynamically softens harsh peaks by emulating high-frequency compression, but without relying on traditional attack and release times. Instead, it behaves more like the natural smoothing effect of tape magnetization.

💡 Why Gold Clip’s bypass-able design makes it a versatile mastering tool, allowing you to use its processors as standalone tools for smoothing clipped or limited pre-masters.

If you’ve ever struggled with mastering loud, limited mixes, this video will give you some new ideas on how Gold Clip might help.

Check it out below:

Have questions? Just hit reply, and we’ll get back to you. You can also tag us on instagram—we’re always happy to connect!

Be well,

Ryan Schwabe

Grammy-nominated and multi-platinum mixing & mastering engineer

Founder of Schwabe Digital

08) Refining High Frequencies with Box Tone

Box Tone is one of the more subtle processors on GOLD CLIP, but I often find it helpful when I want to smooth out the top end of digital recordings. In effect, Box Tone is a hyper-sonic low-pass filter that cleans up some of the digital ugliness on the very top of a mix.

Box Tone is one of the more subtle processors in GOLD CLIP, but I often find it invaluable for smoothing out the top end of digital recordings. Think of it as a hyper-sonic low-pass filter that helps clean up some of the digital harshness in the very highest frequencies of a mix.

While subtle, Box Tone adds a slight contour to the highs, creating a smoother, more cohesive top end—especially when using the Modern setting.

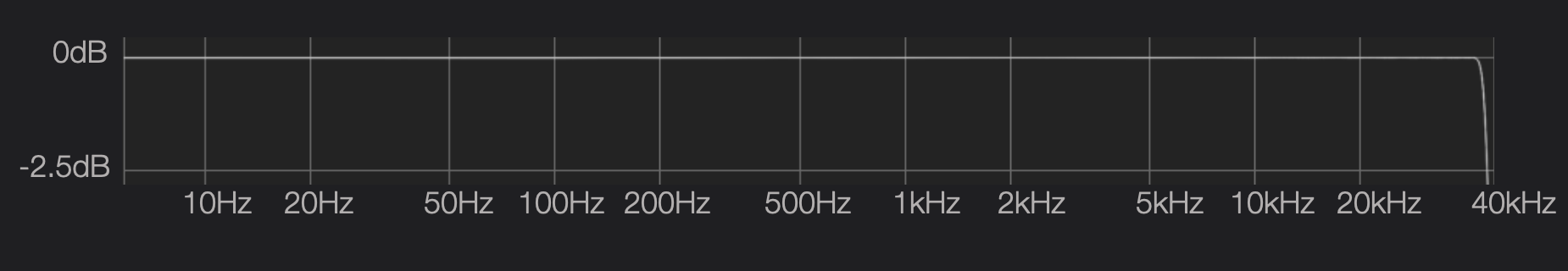

Here’s a look at what Box Tone is doing:

FLAT: The True Bypass Option

When set to FLAT, Box Tone is completely bypassed. There’s no contour or hyper-sonic low-pass filtering applied—it remains true to the input signal all the way up to 40 kHz in a 96 kHz host sample rate session. This setting ensures a completely neutral pass-through, perfect for when you want an unaltered, transparent output.

CLASSIC: Smooth Air-Band Contour

The CLASSIC setting adds a gentle air-band contour around 20 kHz, slightly softening the top end in your mix. It also applies a hyper-sonic low-pass filter, removing unwanted frequencies beyond our hearing range, between 20 kHz and 40 kHz.

This setting is perfect for subtly shaping the high end while keeping the extreme top end clean and true to input.

MODERN: High-End Shaping

The MODERN setting introduces a more aggressive contour than CLASSIC, with subtle cuts around 3 kHz and 8 kHz to reduce harshness and improve smoothness. It also slightly reduces the air-band around 20 kHz by 0.3 dB, adding a refined touch to the top end.

Like CLASSIC, it features a hyper-sonic low-pass filter to remove unwanted frequencies between 20 kHz and 40 kHz, but with a more assertive tonal shaping that’s ideal for modern productions requiring a tighter, smoother high-frequency response.

Box Tone is a high-precision filter inspired by the mid- and high-frequency contours of modern and classic converters. As you’d expect, converters are designed to be as flat and balanced as possible, so these effects are intentionally subtle.

Box Tone captures this nuanced behavior, providing a gentle and refined way to shape the top end of your mix while preserving its natural character.

Hit reply and let me know how you are using Box Tone in your mixes and masters. Or, tag @SchwabeDigital in an instagram story and show us how you are using Gold Clip. We'll repost.

Be well,

Ryan Schwabe

p.s. Subscribe below for updates on Schwabe Digital Plugins.